Should participants use their own smartphone in ESM / EMA studies?

TL;DR

When running experience sampling (ESM) / ecological momentary assessment (EMA) studies, researchers sometimes wonder whether to provide a study phone or rely on participants’ own device. A methodological study shows: using a borrowed phone increases data completeness (suggesting higher engagement), while participants respond faster and more “in the moment” on their own device. Convenience and privacy feel the same either way, so the best choice depends on whether standardization (and engagement) or timing precision matters most.

At m-Path, when we help researchers setting up a new experience sampling (ESM) / ecological momentary assessment (EMA) study, we sometimes get the question:

Do we give participants a study smartphone, or do we let them use their own device? 🤔

On one hand, providing a phone standardizes the experience. Everyone receives prompts on the same device, with the same screen size, same keyboard, same app usability.

On the other hand, handing out smartphones is expensive (especially for a one-off study), complicated, and often requires face-to-face logistics. And what if participants don’t carry the extra device? Or worse: “forget” to return it?

Despite how common this dilemma is, surprisingly few studies have tested how this choice actually affects participant responding, with one notable exception: Walsh & Brinker (2016).

The experiment at a glance

These authors conducted a brief ESM / EMA study with 179 undergraduate students, randomly assigning them to use either their own smartphone or a borrowed study phone.

The protocol was rather short (compared to the “average” ESM / EMA study): Participants received 20 notifications over two days, and each prompt asked them to complete a simple six-item questionnaire.

The researchers wanted to test two competing ideas:

1. The novelty hypothesis ✨

A new device is exciting, maybe participants will engage more.

2. The utility hypothesis 🤳

People are more responsive on a device they already use all day.

What they found

As usual in science, results were nuanced: each hypothesis held part of the truth…

1. Research-dedicated phones increase full response completion.

Participants using a borrowed smartphone were significantly more likely to complete all items on a prompt, and more likely to provide extra (unsolicited) responses.

Of course, this is a somewhat unconventional metric in methodological ESM / EMA research as many platforms often require full survey completion by default, but it suggests that participants may be more motivated and engaged with the study. It’s not unthinkable that this also impacts compliance. However, this has not been explicitly tested.

The authors point to novelty✨: receiving a fresh device can feel like a new toy, and emphasizes the importance of the study.

2. Participants respond faster on their own phone.

Response latency (the time between receiving a prompt and engaging with it) was shorter when participants used their own phone. Median response times differed by several minutes (about 3 minutes on personal phones versus 7 minutes on borrowed phones).

This pattern supports the utility hypothesis🤳: our personal phone is woven into our daily habits, always close at hand (perhaps sometimes more than we like 😅), and checked more frequently. For researchers aiming to capture experiences as they unfold in the moment, this difference in timing can be highly relevant.

3. Privacy and convenience ratings were basically identical.

Across both the borrowed-phone and own-phone conditions, most participants rated the study as “good” in terms of convenience. Similarly, privacy concerns did not differ between groups.

This is reassuring: participants did not experience borrowed phones as creepy, intrusive, or burdensome, even when they had to carry two devices. At the same time, the authors caution that the sample consisted of young adults, a group generally less sensitive to digital privacy issues, so perceptions may differ in other populations.

4. A hidden insight: recruiting participants to borrow phones is surprisingly hard.

One of the most interesting observations in this study wasn’t in the results table but in the procedure.

The authors struggled to recruit participants willing to borrow a phone. Many simply didn’t show up during the intake session. A follow-up survey found:

- 58% said they forgot the appointment

- 23% said the appointment was inconvenient

- 17% switched to a different study, potentially one using their own phone

- only 2 people said they were worried about breaking the borrowed phone

- only 1 person said they didn’t want the hassle of returning it

This suggests that borrowing a phone may not feel useful enough to motivate attendance to an intake session, especially when participants already own a device. This practical friction is important for any ESM / EMA study considering loaner phones.

Why this matters for your research

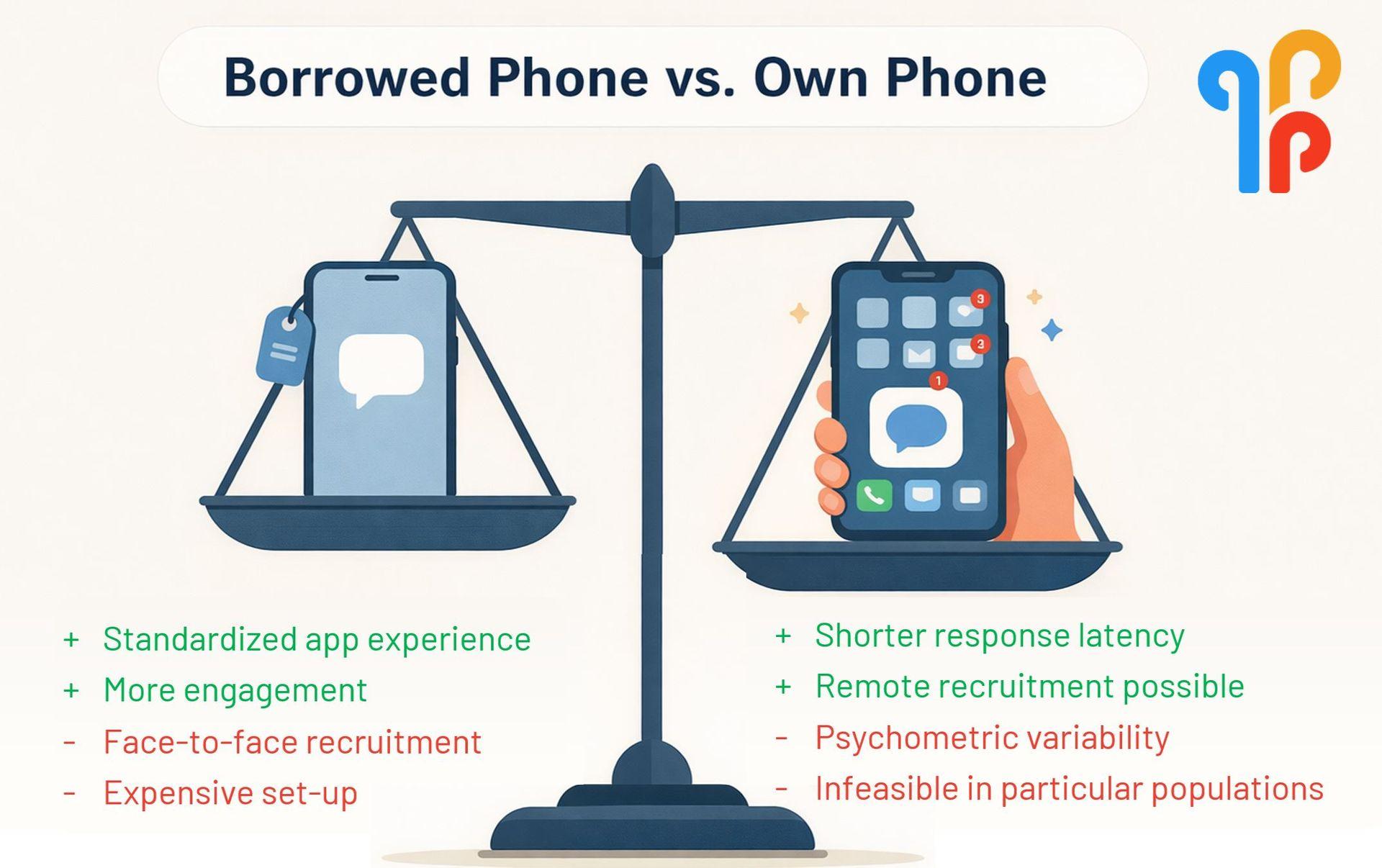

In the end, the choice between study phones versus personal devices comes down to what you’re trying to optimize in your ESM / EMA study.

Borrowed phones may boost data completeness (and perhaps lead to higher compliance?), but they require more logistics.

They are ideal when:

- standardization is crucial (for example when using mobile cognitive tests or sensing)

- screen size differences pose a psychometric risk

- you want to reduce layout-driven response bias

- you have the budget and operational capacity

Participants’ own phones may lead to faster, more in-the-moment responding, but they also introduce “between-device” variability.

They are ideal when:

- timing precision matters and you want participants to respond as close to the prompt as possible

- logistical simplicity is a priority and you want to avoid device hand-outs and returns

- budget constraints make purchasing study phones impractical

- you want to minimize the risk of participants forgetting an extra device

Practical take-aways

This study shows that when designing your ESM / EMA study, you should think carefully about your priority (more complete responses versus faster, more in-the-moment responding), the characteristics of your participant population (for example, youngsters may not be able to use their own device in class), and your operational capacity in terms of budget and logistics.

👉 Explore the full paper here: Telematics and Informatics, 2016.